Techniques

Flamenco is played somewhat differently from classical guitar. Players use different posture, strumming patterns, and techniques. Flamenco guitarists are known as tocaores (from an Andalusian pronunciation of tocadores, "players") and flamenco guitar technique is known as toque.

While a classical guitarist supports the guitar on the left leg, and holds it at an incline, flamenco guitarists usually cross their legs and support the guitar on whichever leg is on top, placing the neck of the guitar nearly parallel to the floor. The different position accommodates the different playing techniques. Many of the tremolo, golpe, and rasgueado techniques are easier and more relaxed if the upper right arm is supported at the elbow by the body of the guitar rather by the forearm as in classical guitar. Nonetheless, some flamenco guitarists use classical position.

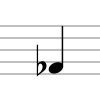

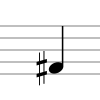

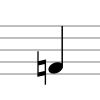

Flamenco is commonly played using a cejilla (capo) which raises the pitch and causes the guitar to sound sharper and more percussive. However, the main purpose in using a cejilla is to change the key of the guitar to match the singer’s vocal range. Because Flamenco is an improvisational musical form that uses common structures and chord sequences, the capo makes it easier for players who have never played together before to do so. Rather than transcribe to another key each time the singer changes, the player can move the capo and use the same chords positions. Flamenco uses a lot of highly modified and open chord forms to create a solid drone effect and leave at least one finger free to add melodic notes and movement. Very little traditional Flamenco music is written, but is mostly passed on hand to hand. Books, however are becoming more available. Both accompaniment and solo flamenco guitar are based as much on modal as tonal harmonies; most often, both are combined. In addition to the techniques common to classical guitar, flamenco guitar technique is uniquely characterized by:

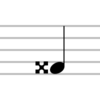

- Golpe: Percussive finger tapping on the soundboard at the area above or below the strings. This requires a golpeador (tap-plate) to protect the surface of the guitar.

- Picado: Single-line scale passages performed by playing alternately with the index and middle fingers, supporting the other fingers on the string immediately above. Alternate methods include using the thumb rapidly on adjacent strings, as well as using the thumb and index finger alternately, or combining all three methods in a single passage.

- Rasgueado: Strumming done with outward flicks of the right hand fingers, done in a huge variety of ways. A nice rhythmic roll is obtained, supposedly reminiscent of the bailador’s (flamenco dancer's) feet and the roll of castanets. The rasgueo can be performed with 5, 4, or 3 fingers.

- Alzapúa: A thumb technique which has roots in oud plectrum technique. The right hand thumb is used both up and down for single-line notes and/or strumming across a number of strings. Both are combined in quick succession to give it a unique sound.

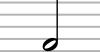

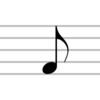

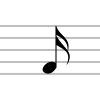

- Tremolo: Rapid repetition of a single treble note, often following a bass note. Flamenco tremolo is different from classical guitar tremolo, it is usually played with the right hand pattern p-i-a-m-i which gives a 4 note tremolo. classical guitar tremolo is played p-a-m-i giving a 3 note tremolo. Or it may be used as an ornament to a chord, in which case it is done on the highest chord string finishing with a thumb across all the strings that make the chord. This creates a very quick trill followed by a full bodied thumb.

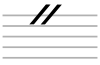

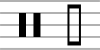

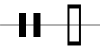

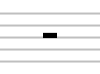

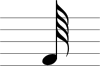

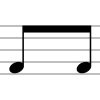

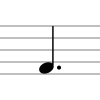

Flamenco guitar employs a vast array of percussive and rhythmic techniques that give the music its characteristic feel. Often, eight note triplets are mixed with sixteenth note runs in a single bar. Even swung notes are commonly mixed with straight notes, and golpes are employed freely and frequently, as is strumming with the strings damped for long passages or single notes.

More broadly, in terms of general style and ability, one speaks of:

- Toque airoso ("graceful"): lively, rhythmicm, with a brilliant, almost metallic sound.

- Toque gitano o flamenco ("Gypsy" or "flamenco"): deep and very expressive, using a lot of grace notes and countertempos.

- Toque pastueño (from a bullfighting term for a calm, fearless bull): slow and peaceful.

- Toque sobrio ("sober"): without ornament or showing off.

- Toque virtuoso: with exceptional mastery of technique; running the risk of excessive effects.

- Toque corto ("short"): using only basic technique.

- Toque frío ("cold"): the opposite of gitano or flamenco, unexpressive.

.

.